Q&As

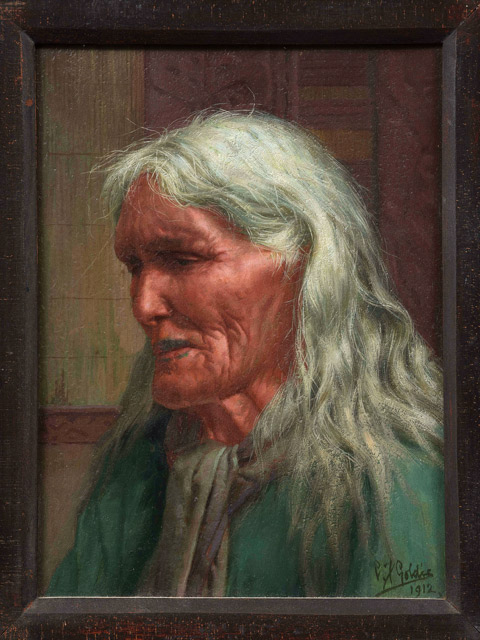

Keep Goldie in the family?

QReading your Q&As on dividing inheritance reminded me of a recent Seven Sharp segment about New Zealand art sales at the International Art Centre. To my surprise, a family heirloom—a Goldie painting we believed would stay in the family—was among the works auctioned. It had been passed down from my great-grandfather, with the expectation that it would be treasured and preserved. While his son upheld this, the next generation chose to sell it.

This shows how assumptions about inheritance can unravel if intentions aren’t clearly documented. Times are changing — where previous generations valued legacy, financial considerations now often take precedence. Without explicit legal provisions, even items of deep cultural and historical significance can be lost.

While we cannot change what happened, this serves as a reminder that estate planning must evolve. If something is truly meant to stay in a family, it needs to be clearly stated — because unspoken wishes, no matter how obvious they seem, may not be honoured in the future.

AIt must have been a shock to see the family treasure up for sale. Trouble is, such a situation can’t be remedied by simply saying in a will — or a letter with the will — that an item may not be later sold.

“The question of ensuring that an heirloom remains in a family is tricky,” says Auckland lawyer Greg Presland. “Generally if a chattel is bequeathed to a family member they own the item outright and, as it is theirs, can sell it if they wish.

“The item could be held in trust for a number of beneficiaries. The complexity of the ownership would mean that it would be more difficult to sell the item, and also that family members would have a say in what happened to the item,” he says.

“If I was asked to make it as difficult as possible for a Goldie to be sold, I would give it to all of my whanau members and indicate my preference that if at all possible the item not be sold but is kept within the family’s ownership.”

Then there would, of course, be the issue of who hangs the painting in their house? Perhaps it could move around from year to year.

Living on NZ Super — and saving

QWe are retired and have $60,000 left in our KiwiSaver. We have $200 a fortnight spare from our NZ Super. Would we be better off putting it into our KiwiSaver or a bank account?

AGosh! At a time when many say it’s miserable living on just NZ Super, you have a considerable amount left over.

I wrote to ask how you get by, and here’s your reply: “Our fortnightly income consists of: $803 each, NZ Super — total $1,606; $155 disability allowance; $100 board from daughter who lives with us on a jobseeker with medical exemption I think it’s called. She also buys some food. That totals $1,861.

“Fixed expenses: $1,232, including $500 for food and petrol. That leaves $629 a fortnight.

“Incidental expenses: doctors, $19.50 a visit, six or seven times a year; coffee group $25 monthly but generally less; haircuts $50 every 3 months or so, I do my own; clothing generally op shop or hand me downs, $150 a year?; birthday and Christmas for five grandchildren $400 a year.

“We have no outstanding debt or credit card debt.”

Clearly you have a mortgage-free home, which helps hugely. And perhaps your daughter’s contribution helps, although her extra expenses might offset that.

Then there’s the disability allowance, but it’s not a lot, and presumably your costs are a bit higher because of the disability. We should note here that many retired people receive the accommodation supplement or other government payments above NZ Super. See this page.

Your frugality on clothing and haircuts clearly helps, and you’re not big spenders on food. Good on you! It sounds as if you don’t go out often, but presumably you’re content with that.

So … what should you do with the extra $200?

Assuming you’re over 65, you can withdraw from your KiwiSaver account whenever you want to — although it might take a few days.

If you’re in a higher-risk growth or aggressive fund, or even in a balanced fund, your balance will fluctuate — although over the longer-term it will probably grow more than in a conservative or defensive fund. But I’m guessing you’ve gone for lower risk — which is the best spot anyway for money you expect to spend in the next few years. And you never know when you may want to spend it — hopefully on a treat every now and then.

So which is better for your unspent cash — a bank account or your KiwiSaver fund? Returns will probably tend to be a bit higher in KiwiSaver — although if you use bank term deposits, they’re likely to be similar. For more on this, read on. The correspondent is writing about non-KiwiSaver funds, but if you’re over 65 the two types of funds are pretty much the same.

Funds or term deposits?

QI respect you as a source of commonsense advice, untainted by commercial associations.

I’ve been looking at “conservative” investment funds — i.e. the cautious end of the managed investment spectrum. Averaged over five years, most of these funds deliver returns well below 3 per cent. According to the Sorted website, the average return over all funds is 2.38 per cent.

What incentive is there to put savings in managed funds when bank deposits are yielding more than 4 per cent? Am I missing something?

AYou’re missing a few things. But first, let’s compare apples with apples.

Returns on bank term deposits don’t fluctuate throughout the period. Meanwhile, returns on the conservative funds in the Sorted’s Smart Investor tool can fluctuate quite a lot.

That’s mainly because 10 to 35% of their investments are growth assets — usually shares and sometimes property — whose values rise and fall with markets. But also, many of their investments are bonds. And bond values also fluctuate, when interest rates move.

Let’s say a fund buys a newly issued five-year bond paying 4% interest. If, during those five years, interest on similar bonds rises to 5%, a 4% bond will lose its appeal and its market value will fall. Conversely, if interest rates fall, the bond’s value will rise.

In the last few years, interest rates rose unusually fast, although they have fallen since. For a while that meant negative returns on managed funds holding bonds. In the last year or so, with interest rates heading back down, returns on these funds have recovered. But their average five-year returns on Smart Investor are still affected.

To make a closer comparison with term deposits, look at defensive funds on Smart Investor, which hold less than 10% growth assets. Many hold bonds — so have still suffered recent negative returns. But if you sort the defensive funds by “Growth assets (lowest first)” (the default setting) the first funds listed include several with the word “cash” in their name.

By clicking on a fund’s name, you can check its asset mix. The funds that invest only in cash are the ones to compare with term deposits. In fact, their investments are typically term deposits or very similar.

So, if we look just at those funds, their average returns over time should be pretty close to those on bank term deposits — although they might be somewhat lower for these reasons:

- Tax. The returns on Sorted are after fees and after tax at the top PIE rate of 28%. Returns on term deposits are before tax, and that makes a big difference. If you’re in the 33% tax bracket, a TD return of 6% becomes 4% after you’ve paid the government. A 4.5% return becomes 3%. What’s more, managed funds are PIEs, so many people pay lower tax than on TDs.

- Different time periods. The “headline” returns on Smart Investor are for the five years ending September 2024, which included huge volatility. The TD rates you’re looking at are for future periods.

In the years ahead, returns on TDs and cash funds will probably be about the same. In fact, because funds invest millions of dollars, they may get better interest than we would.

Note too that in non-KiwiSaver funds — or in all managed funds for 65-pluses — you can withdraw your money with just a few days’ notice. Not so in TDs. There are times when this could be a big plus.

By the way, if you’re over 65 you’ll get a wider choice if you include KiwiSaver funds. And these tend to have slightly lower fees than non-KiwiSaver funds.

Rule for early retirees

QI’ve been reading the correspondence about how much savings are required when you retire. I am fortunate to be able to retire early. Is there a rule of thumb for how much you can spend per week for each $100,000 saved if you retire at the age of 60?

AYou will have seen the rule of thumb in the column recently: If you retire at 65, you can spend $100 a week for every $100,000 you have in savings, and your money will probably last into your nineties.

But what about somebody who retires at 60 — or for that matter at 70 or 80?

The NZ Society of Actuaries has written about four Drawdown Rules of Thumb, two of which work well for any retirement age:

- The Fixed Date Rule: Decide how many years you want your money to last. At 60, you might choose 30 years, assuming you will be okay with just NZ Super from age 90 — as many people are.

Each year withdraw the current value of your savings divided by the number of years left. Your income will vary each year, depending on returns on your savings — although you could withdraw a bit more some years to make up for the fact that returns are unusually low, and a bit less if returns are unusually high

- The Life Expectancy Rule: Each year withdraw the current value of your retirement fund divided by your average remaining life expectancy at that time. StatsNZ publishes that info. Again, the amount will vary each year.

You can read about these and the other two rules here. They’re written for non-experts.

Footnotes:

- You can estimate your life expectancy taking into account your own situation by using the online Northwestern Mutual Lifespan Calculator. You have to convert your height to feet and inches and your weight to pounds, but that’s easy online. The calculator takes into account whether you drink, smoke, exercise, use a seatbelt, drive safely and so on — and you can see how modifying those behaviours would change how long you’re likely to live. It’s fascinating.

- I’ve still got several Q&As to run about spending in retirement. Keep reading over the next few weeks!

- On a lighter note, a friend sent me this: “I did some financial planning, and it looks like I can retire at 97… and live comfortably for 11 minutes.”

Houses v KiwiSaver

QThe constant rise in house prices annoys me. Why isn’t the prospect of falling house prices a good thing? Ultimately high house prices (and rents) affect poverty levels, health and wellbeing, inflation, and run-on effects like poor education, crime etc.

At the end of the day if you own a million-dollar house you will need to pay a million dollars for a similar house if you move. If the house that you owned fell by half a million, so does the house that you want to buy, so it’s all even.

Rumour has it that the average house price doubles every 10 Years. This paints an alarming future. If the average price is $800,000 now by 2035 it would be $1.6 million and by 2045 $3.2 million.

To get to my point, no KiwiSaver investment is going to keep up with that.

AHouse prices haven’t actually risen constantly. You wrote before last week’s column was published, with a graph showing average prices fell 18% in the last few years. It’s funny how people overlook that.

Still, I agree that homeowners don’t really gain when house prices rise — although landlords do.

Your rumour is a little exaggerated. The Reserve Bank House Price Index grew by 90% in the ten years ending September 2024 — the most recent data. In the decade before that, it grew by 63%, and in the one before that by 97%.

But if we accept your doubling in 10 years, under the Rule of 72 — covered in this column before — you divide 10 years into 72, to give us a return of about 7.2% a year.

Meanwhile the latest Morningstar KiwiSaver Report tells us ten-year average returns, after fees but before tax, were 9.3% in aggressive funds, 8.3% in growth funds, 6.7% in balanced funds, and 4.7% and 4.2% in the two lower-risk categories. So yes, if you can put up with the volatility of a higher-risk fund, your investment may outpace house prices.

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let’s keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm, ONZM, is a freelance journalist, a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. She is a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL) and a former director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won’t publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.