Q&As

- How different is it this time?

- Is this a good time to subdivide?

- Was I too tough on last week’s mother?

- Is gold a good investment these days?

- How would bank deposit insurance work for term deposits?

- Bank credit ratings vary — and should you move money to Australia?

- Pay down mortgage with bank deposits — especially if nervous

QI question your advice during this pandemic/economic crisis. The mantra “stay in shares for the long run” doesn’t work in a long-term crisis. Nobody doubts there will be huge job losses.

Shares will decline for months not weeks, so people with limited capital will minimise losses by switching super funds to cash until prospects are clearer.

The same is true of housing. When many people lose jobs, house prices will drop — that’s inescapable reality. A generation of young people with average jobs have missed out on owning a home, while older people made hundreds of thousands for nothing. Investors piled into housing to create a self-fuelled boom, then refused to sell for less than “what it’s worth” at the unsustainable peak.

Young buyers should do the same — refuse to buy until the lack of buyers forces house prices down to where families can afford them.

These are not normal times. Don’t you have any doubts about offering “normal” advice to people who can’t afford to lose more than they already have, after years of stagnant real incomes and high rents?

AThey say that the four most dangerous words in the financial world are, “This time it’s different.”

People tend to think, when markets are rising or falling particularly fast, that the usual braking won’t happen. But if you look back, it always does. The tech boom that people said would “go on forever” collapsed. The global financial crisis that was “unlike anything before, and unstoppable” stopped.

True, this Covid-19 market downturn seems “extra different”, with governments giving priority to health over economics — and rightly so. And I’m not denying there will be big job losses.

But I define the long run as ten years or more. And no expert is saying that it will be anything like a decade before we’re back buying goods and services from most current companies — as well as some new ones.

Even the Great Depression of the early 1930s lasted only a few years, and economists know so much more now about how to avoid prolonged downturns.

I’m not saying this is not a big deal. Just that it’s not the end of the financial world as we know it.

But you’re a lot more confident than I am about one thing — your ability to forecast that shares will decline for months not weeks. I really don’t know.

Share prices don’t fall and rise with economies, they fall and rise with people’s expectations of what economies will do in the near future.

If the professionals who do most of the share trading — the people who run KiwiSaver funds and the like — think companies will perform badly in the months to come, they sell those shares now. That’s what happened in late February and early March.

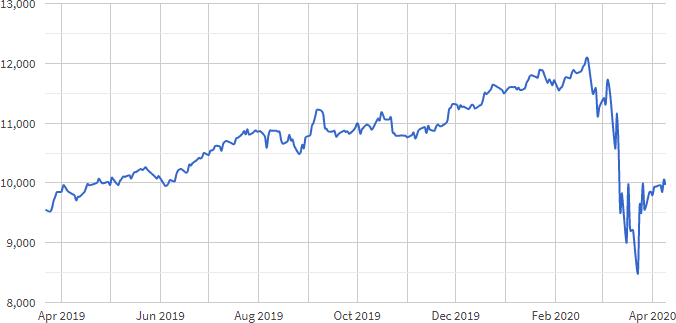

NZX 50 Index

But since March 23, enough people have apparently thought that investors over-reacted, and have started buying again, as our graph shows. As I write, the NZX50 index has regained more than 40 per cent of what it lost from late February to late March — something I think a lot of people don’t realise.

Of course by the time you read this, the NZ market might have turned downwards again. Who knows?

In any case, I disagree that most people should at this stage move their retirement money to cash.

You’re right that that would minimise further losses. And I’ve always said that people who can’t bear the thought of their savings balance dropping should stay in cash or the lowest-risk defensive funds.

But they pay a pretty big price for that security. Over periods of ten years or more, people in higher-risk funds almost always end up with more, usually much more.

The other factor in risk choice is when you plan to spend your savings.

Money that you expect to spend in the next few years should have been in low risk already. If it’s not, move it gradually. And spending money for three to ten years should be in a bond fund or balanced fund.

But if you have ten years or more to go, I still say stick with a higher-risk fund if you can tolerate volatility. If you’re not sure about that in the current climate, try putting at least some of the money in higher risk and watch how you cope with the ups and downs.

House prices are a different issue. All the experts seem to think they will fall a bit, although nobody I’ve read is predicting a drop of more than 10 per cent. So it’s probably not a bad idea for would-be new homeowners to wait a while.

But with house purchases there are usually other factors to consider — buying before a baby is born, wanting to establish a garden, no longer wanting a landlord to control your life, and so on.

As I said three weeks ago, people with strong job security and financial backups who are keen to buy might be able to bargain hard in the current environment — once we are free to again walk through houses for sale.

Don’t get stuck on buying at the bottom of a house price dip that nobody can pick anyway. Get on with your life.

By the way, you write of years of stagnant “real” — or inflation-adjusted — incomes. Not so. According to the Reserve Bank’s inflation calculator, over the last ten years inflation was 17 per cent while wages grew 30 per cent. Over the last two years, inflation was 3.8 per cent while wages grew 6.9 per cent.

QWe have a family home sitting on a large section that is easily subvisible. Our adult kids have talked about subdividing it for years.

Given that two of our kids are in some financial difficulty with the coronavirus lockdown, would now be a good time to consider subdividing our land to free up cash to help them?

AProbably yes. As I said above, economists are predicting a fall in property prices, so get in now.

Just as importantly, you have other reasons for selling now. This is a good example of the family factors I was talking about when it comes to property buying and selling.

Don’t rush to sell, though. You’re likely to get a lower price if you feel under pressure. If your offspring need urgent financial support, you may have savings you can lend them in the meantime, knowing the subdivision proceeds will come eventually.

QMy pennyworth on your encouraging last week the 21-year-old to have her mother jump back, boots and all, from the cash to the growth fund.

Her precipitous switch reaction suggests her earlier 100 per cent growth fund exposure, whilst logical for many late thirties, was probably always too high-risk for her, there being no disgrace in acknowledging that.

You’ve been steadfast Mary over the years at emphasising that the real trick for “small investors” is not to let fear shake them out of plummeting sharemarkets, all too often near the bottom. Is it possible that your devotion to that message has prompted a bit of a kneejerk reaction to this woman’s circumstance?

My recommendation would be to immediately switch back — but only, say, 40 per cent into the original growth fund and split the rest between cash and balanced.

From that position she’d be able to then talk to her daughter or do research so as to become more confident about her true tolerance for volatility and thus her most suitable fund choice.

Were she then to decide that she was “moderate”, she could consider feeding some of the cash fund equally over the next year or two, in evenly spaced tranches, into the balanced and growth funds.

AGood point. In my reply last week I should have taken more note of the mother’s apparent nervousness about the drop in her KiwiSaver balance.

I think and hope, though, that she and many others in KiwiSaver who have never seen much of a downturn before will try to get braver, and park at least some of their savings in higher risk.

QIn your March 28 Herald edition, you say about gold, “absolutely not”.

I’d like to argue that even gold, when invested over time at a consistent amount, can be beneficial in one’s portfolio, even if it’s just to help you sleep at night.

After all gold like houses will always have some value — but without the tenants.

Per the attached spreadsheet, if you invested $10,000 every six months for the last seven years with a 2.5 per cent annual increase, your gold would be worth $261,000, while the same investments in the top 50 NZ shares would be worth, before Covid, $243,000 and after Covid, $192,000.

You may argue that gold has had a recent rally, and the NZ dollar has dropped. But even dropping gold to $US 1450 per ounce, and raising our dollar to 0.65, that still gives you a healthy $212,000.

Like all things gold will trend up eventually.

New Zealand has been saved from Covid catastrophe by pumping more billions into debts, and bringing interest rates close to 0 per cent. We now stare down the barrel of negative interest rates. A 10 to 20 per cent portion of your portfolio in gold may not be such a bad idea after all.

AI’m not totally convinced.

In the column two weeks ago I said "absolutely not" to someone who has $500,000 in bank term deposits that he can’t afford to lose. He was worried that banks might be about to collapse. Hardly a gold investor! But is it a bright idea for others?

While your numbers look roughly right at first glance, I’ve got several issues:

You acknowledge that you’ve been lucky with the period you chose, in that gold rallied recently and the Kiwi dollar has fallen.

But there’s more to it than that. The particular pattern of prices suits you well. You’re drip feeding money in and buying gold cheaply early in the period, and then valuing it at a high price at the end. If, instead, you had invested the whole lot in early 2013, you would be losing now, as our graph shows. And what if you had put the lot in at the 2011 peak?

And you underplay the big drop in the exchange rate between the New Zealand and US dollars over the period — from about 80 to 60 cents. That greatly affected your results. In any future period, the opposite could occur.

Also:

- You ignore dividends, which is like ignoring rent when you look at a property investment. And it makes a particularly big difference when we’re looking at NZ shares, which tend to pay higher dividends than in other countries.

- You ignore tax, which favours NZ shares over gold. A tax expert tells me that after taking dividends and tax into account, we should add $35,000 to the shares and subtract $30,000 from the gold.

- You ignore fees. These can be low for shares if you use an ETF (exchange traded fund) or index fund. For gold, either you have to pay for storage or you invest in a gold ETF and the manager has to pay for storage — a fee that is typically 1 per cent.

By the time we adjust for all that, NZ shares beat gold over the period. And that’s over a particularly strong period for gold!

Another problem with gold is that you don’t receive any ongoing income — like interest, dividends or rent. You have to come up with other money to pay your tax.

Gold is particularly favoured by some people in unsettling times. They make comments like yours, that it will always have value — whatever happens to a government or an economy.

That’s true, but if you put the bulk of your savings in gold and later need to turn it into spending money, it will be worth only what somebody else wants to pay for it at that time. It’s quite a gamble.

What if you put just your suggested 10 or 20 per cent of your investments in gold? That does give you some diversification, but it’s not going to make that much difference if the rest of your savings either plummet or soar.

If holding some gold helps you sleep at night, go for it. But it’s not for the nervous March 28 correspondent, and I think I’ll give it a miss!

QI have $150,000 in a number of term deposits held at a single prominent bank, maturing at six- to eight-week intervals through to late 2021. I try and reinvest as much as possible as each one matures.

My questions are:

- If a deposit insurance scheme is introduced, how would my term deposits be treated? Would they be subjected to “the treatment” en masse or one by one?

- In these circumstances would I be better off distributing the term deposits with the other banks?

- I am also concerned that Quantitative Easing and its relatives will push so much money into the system that either hyperinflation, or perhaps worse, hyper-deflation occurs. In the latter case may it mean that house prices could fall substantially?

By the time I leave my beloved home on the water I would like to think that between sea level rise (maybe a metre in the next 30 years) and deflation that it might be worth something to my heirs.

What do you think?

AFirst we’ll set the scene. Last December the government said the deposit insurance scheme was not expected to be in effect until 2023 at the earliest.

But in last weekend’s Herald, Reserve Bank Governor Adrian Orr told Liam Dann that work is being accelerated on deposit protection, so it might happen sooner.

In the meantime, we’re operating under Open Bank Resolution, or OBR. This means that if a bank fails, a portion of all accounts would be frozen, and you may not get all that money back later. But the bank would stay open, and a “de minimus” amount in each transaction account would not be frozen, so everyone could continue their day-to-day banking.

Okay, let’s look at your questions. Finance Minister Grant Robertson said in December that “deposits will be insured up to a limit of $50,000 per depositor, per institution.” So all your deposits would be treated “en masse” as you put it.

Robertson added, “This limit would fully cover the vast majority of depositors, thought to be 90 per cent or more.” But not you, with your total deposits easily exceeding $50,000.

However, he said, “depositors could obtain coverage for more than $50,000 by splitting their savings across accounts held at different deposit-taking institutions.” So yes, it would be wise to spread your money around.

The same advice applies under the current OBR scheme. If a bank fails, “the same proportion of funds is frozen for someone with five $10,000 TDs and someone with one $50,000 TD,” says a Reserve Bank spokesperson. But it would be different if you were in lots of different banks, which won’t all fail at once.

On your third question, the spokesperson says, “The Reserve Bank has implemented a number of measures to support the New Zealand economy and ensure the financial system is functioning well during these testing and uncertain times.

“The Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP) programme will buy up to $30 billion of New Zealand Government bonds in the secondary market over a 12-month period. Also known as Quantitative Easing or QE, the programme will lower borrowing costs for households and businesses and inject money into the economy and build confidence.”

On your inflation and deflation worries, he says that QE “is designed to help meet our monetary policy objectives of low and stable inflation and supporting full employment. The Reserve Bank will closely monitor the programme, and modify it as needed.”

“There appears little risk of hyperinflation given the sharp fall in economic activity due to coronavirus, while the initiatives announced by the Reserve Bank and Government will mitigate deflation impacts and help support the economy, prices and jobs.”

I hope that’s comforting.

QI read that the Government intends to introduce deposit insurance cover for my money in banks, but only to a maximum of $50,000 per bank.

I am not sure if the Government has thought this through as my reaction will be to move my money so I have no more than $50,000 in each bank. This will involve moving the money from the big banks to the minor banks with lower credit ratings.

I have been considering moving money offshore to Australia where the insurance covers $250,000 per bank. We are clearly the poor cousins, yet again. What are your thoughts Mary?

AYou’re right that if you move your savings beyond the big four banks you’ll be, for the most part, in institutions with lower credit ratings.

For information on this, go to the Bank Financial Strength Dashboard on the Reserve Bank website.

Among other things, it lists the New Zealand banks’ credit ratings from three agencies. Their findings vary:

- S&P gives our big four banks — ANZ, ASB, BNZ and Westpac — the highest New Zealand ratings, followed by Kiwibank and Rabobank. Other banks, including the Co-operative Bank, Heartland, SBS and TSB, are not rated.

- Fitch gives Kiwibank a higher rating than the big four. Below them comes TSB, and below that Co-operative, Heartland and SBS on the same rating.

- Moody’s gives equal ratings to Kiwibank and the big four. It doesn’t rate the others.

Over all, Kiwibank seems to be up there with the big players. Beyond that, it’s up to you whether you want to take a bit more risk with some of the smaller banks.

Keep in mind, though, that Orr said in last weekend’s paper, “People just have to know that we are sitting here with the best banking system in the world.” Orr’s credibility is at stake here. He wouldn’t say that if he was worried about New Zealand banks’ viability.

If you disagree, though, you can indeed move money to an Australian bank. That will bring with it complications with tax, foreign exchange rates and perhaps inheritance issues. I wouldn’t bother, but I’m not saying you shouldn’t.

QWe have our freehold family home and an investment property with a $200,000 mortgage, and $350,000 in short-term deposits in the bank.

With the current global financial situation, we are concerned about the banks getting under pressure due to possible future corporate defaults and mortgage holders losing their jobs. Last thing we want is the banks to default and all we get back is $50,000 from the Government guarantee scheme.

Would it be prudent to pay off the mortgage on the investment property, as we feel it may be safer in the medium term in case of total global financial collapse?

We are both in our late 60’s early 70’s and would still be able to live comfortably in our freehold home for the next 10 years.

AYou and several others who have written assume the $50,000 bank deposit insurance is in place. It’s not yet. See above.

Anyway, on to your question. In ordinary times, holding money in bank term deposits while also having a mortgage doesn’t make a lot of sense — apart from having emergency money.

If you pay off a mortgage, that’s the equivalent of earning the mortgage interest rate, after fees and taxes, on that money. In your case the mortgage interest would be tax deductible, because it’s an investment property. But still you would probably do better paying it down than investing in bank term deposits, which are of course taxed.

What’s more, you’re nervous about the current environment. That strengthens the argument. So yes, pay off that mortgage.

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let's keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm is a freelance journalist, a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL), a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. From 2011 to 2019 she was a founding director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won't publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.