Q&As

- Daughter, 21, puts her Mum right on switching KiwiSaver funds

- Son seeks research on trading versus buying and holding shares, to convince Dad

- Got your visa? Get into KiwiSaver

- Don’t wait until markets recover

- Is it wise to take a “mortgage holiday”?

- Are different bank accounts treated differently if “haircut” happens?

- Should retiree try his luck again on timing the market?

- 20-year-old should get into share market cautiously

- Moving to higher risk is a good move

QMy mum had her KiwiSaver in a growth fund, and last week she changed it to a cash fund after seeing a loss of $20,000 as a result of the Covid crisis. I told her, “Listen to Mary before you do anything”, but she didn’t.

Now that I have shown her all of your warnings (after months of tirelessly suggesting your podcast) it is too late, the damage has been done.

Her and my step dad (who didn’t bother to change) are only 36 and 37. They own their own home and therefore will not be touching KiwiSaver for another 30 odd years.

The question now is: should she quickly change back to the growth fund and cut her losses, or just sit tight in this new fund?

P.S. I’m 21, I’m investing, I’m paying off my car loan ASAP and I listen to the RNZ Your Money podcasts religiously. I also went out and got “Rich Enough?” the other day. I love it.

AThis makes a change from parents worrying about their children’s finances. And the next letter is about a young man trying to educate his Dad. They go with the theme of adult children scolding their parents for being too slack about self isolation. I love it!

The good news is that there won’t be too much damage if your Mum moves back into her growth fund fast.

As it happens, the New Zealand and world share market indexes have tended to inch up in the last week or so — at least by my deadline time. So your mother may miss out on a small gain. But that’s minor.

It’s much more important that she doesn’t miss out on what’s sure to be a better performance in her growth fund over the next 30 years.

Do warn her, though, that the growth fund will fall again sometimes — perhaps even the day after she switches back. She must ignore the downturns. In investing — unlike in most other activities — negligence is good. Your stepfather had it right.

By the way, well done you! There are not many 21-year-olds who are so “together” financially — especially when they didn’t pick it up from their parents.

QI just read your article last week that mentions, “I’ve seen many studies over the years comparing the average investor who moves their money around with the one who buys and holds. The latter always wins.”

Could you please name a couple of studies. I am having a lot of trouble explaining it to my completely property-based father.

ALet me just say first that I was writing about the average “mover”. I added, “Sure, a few movers will outdo everyone else for a while, but that’s just luck. They get over-confident and try it again — and lose.”

Okay, now some research that shows this:

- Brad Barber and Terrance Odean of the University of California looked at the trading of more than 60,000 US households through a discount broker from 1991 to 1996.

The average household return was 15.3 per cent. Sounds great, but in that buoyant period the market gained 17.1 per cent.

This is old research, but it’s particularly interesting because Barber and Odean also found that the more people traded, the worse it was. The fifth of households that traded most gained only 10 per cent a year.

- More recently, a US independent research firm called Dalbar regularly looks at how the typical investor in US stock funds has performed compared with the S&P 500 market index. Each year the results are similar.

In the 30 years to the end of 2019, the investor made 5.04 per cent a year, compared with 9.96 per cent for the index. That’s a huge difference. Starting out with $10,000, the investor would end with $45,000 while the index would end with $196,000.

It’s true that in an S&P500 index fund, your performance wouldn’t be as good because of costs. But you would still easily beat the average investor.

Says Dalbar president Louis Harvey, “Our research consistently shows that the average investor has displayed a strong tendency to sell at just the wrong time whenever there’s a lot of sudden market volatility.”

Online you’ll find other research that suggests traders can do well. But check who is saying that. It’s always people who gain from others’ trading. I’ve been watching this for decades.

The last word goes to Wikipedia on “market timing”, “Studies find that the average investor’s return in stocks is much less than the amount that would have been obtained by simply holding an index fund consisting of all stocks contained in the S&P 500 index.”

What’s its source for this statement? No fewer than five pieces of research. You or your Dad might want to look them up.

QWe have just been granted the Permanent Residence Visa in NZ and so we can enrol in KiwiSaver. But, would it be wise to start investing now that the share market is down, or should we wait a few months when the Coronavirus is over?

AGet in now. Nobody knows whether the markets will fall further. But in the long run — and possibly the short run — they will recover. You might as well be in for that recovery.

QI am wanting to begin investing outside of my KiwiSaver. I have $5000 to start with and will make ongoing contributions in a growth fund or ETF, as it is for the long term.

With the markets being so low at the moment is it better to wait until things recover a bit before starting out?

ALike the previous correspondent, you shouldn’t wait. You’re contributing regularly, so if the markets continue downwards for a while, think of it as buying at low prices!

I saw some data recently on the ten biggest falls in the US S&P500 index since the 1987 crash. The falls ranged from 22 per cent to 8 per cent, and the time it took for the index to recover ranged from just one month to 21 months. An interesting feature: there was no correlation between the size of fall and the time to recover.

A few weeks — or a few years — from now, you’ll be glad you moved.

QEmail from NZ Bankers’ Association: We’d welcome your thoughts on the pros and cons of deferring mortgage repayments. That might help people considering this to work through their options and what it means for them financially.

AWhile you’re not calling this a mortgage holiday, most people are. And that’s a worry.

Last year the government switched from KiwiSaver “contributions holidays” to “savings suspensions” because “holiday” has too many good connotations. For the same reason, I’m going to use your term — mortgage deferrals.

The deferrals, being offered by all retail banks, let people skip mortgage payments for up to six months if they’re in financial trouble because of Covid-19.

But you don’t get something for nothing. You’ll still be running up interest on the loan, so it will be growing. Years down the track, you’ll be repaying the mortgage for longer and paying more total interest.

I’m not saying don’t take advantage of a deferral if you need to. But most people will be spending less for the next while — on travel, entertainment, clothes, hair and so on. And I hope most have rainy day money to draw on.

So even if your income drops, do your best to make mortgage payments for as long as you can. And if you must take a deferral, try to do it for fewer than six months.

A halfway option is to switch to paying interest only for a while. At least, then, your loan won’t be growing. How much difference this will make depends on how long you’ve had the mortgage.

If you have the usual “table” mortgage — with the same repayments throughout, apart from interest rate changes:

- In the early years your payments will be largely interest. Switching to interest-only will make little difference.

- In the later years, your payments will be largely principal. Switching will make a big difference.

Statements from your lender should show how much of each payment is interest. Or ask the lender.

Your lender might also allow other options, such as extending the term of the loan from, say, 20 or 25 years to 30 years. The mortgage calculator on sorted.org.nz shows you how this will reduce your payments.

However, when things come right, please move back to your current mortgage payments. The sooner you get rid of your mortgage, the sooner you can start serious retirement saving, and the more fun you can have as an oldie.

QIt would be good for readers to understand how the banks treat ordinary deposits compared to term deposits on their balance sheets.

Perhaps you could confirm whether depositors and term depositors are both creditors with the same liability for the “hair cut” if a bank gets into difficulties?

Lastly, I recently tried to confirm who the ultimate holding company is for ANZ Bank New Zealand Ltd. Using the NZ Companies Office website and digging deeply through the different entities I found it is ANZ Funds Ltd, which is a private company based in Victoria. How do New Zealand authorities wield any power over this Australian private investment holding company?

AAs explained last week, under Open Bank Resolution (OBR), if a bank failed a portion of all types of accounts would be frozen, and you may not get all that money back later. Each account might suffer a “haircut”.

On your first question, a Reserve Bank spokesperson says, “Depositors, whether they have on-call transactional accounts or term deposits, belong to the same class of liabilities with the same exposure to the haircut (i.e. in terms of proportion of funds frozen) if a bank gets into difficulties and OBR is applied.”

However, a “de minimis” amount in on-call transactional accounts such as cheque and savings accounts wouldn’t be affected, so that people could get on with day-to-day transactions and the bank would stay open.

“Does that mean,” I asked, “that someone with tens of thousands of dollars in a bank would be better off moving all the money into various on-call accounts?” You would get lower or no interest, but these days interest rates are really low anyway.

The Reserve Bank declined to give financial advice. But, the spokesperson said, “Please also note that OBR was designed to enable depositors to access a good portion of their funds (remaining after the application of the de minimis and haircut). In the absence of OBR, depositors would wait for the liquidation of the bank’s assets to access their funds.

“The de minimis amount is currently unspecified but is expected to be around $500 to $1000 on transactional (on-call, chequing) and savings accounts, on a per account basis.”

It doesn’t seem worth rearranging your accounts. In any case, an OBR does not look imminent.

“Open Bank Resolution can only take place on the recommendation of the Reserve Bank with the agreement of the Minister of Finance,” says the spokesperson. “This recommendation is made only in the extreme case when a bank has failed (for example, it is insolvent or unable to pay its obligations) and options have been exhausted to resolve the bank’s problems.

“The Reserve Bank maintains a close watch on the financial system, and wishes to stress that the New Zealand financial system remains safe and sound.”

On your question about ANZ, he says, “The immediate parent company of ANZ Bank New Zealand Limited is ANZ Holdings (New Zealand) Limited. The ultimate parent bank and ultimate holding company of ANZ Bank New Zealand Limited is Australia and New Zealand Banking Group Limited (an Australian bank). The Reserve Bank is the prudential regulator of ANZ Bank New Zealand Limited and we have a range of powers that can be applied to this company.”

More on this topic next week.

QMy wife and I have both recently retired, aged 70. We are both healthy and consider ourselves extremely fortunate. We are mortgage-free and intend to remain in our home until we die. We also own a seaside cottage worth about $400,000. We intend to divide our home into two flats, live in the larger one and rent the other.

I have approximately $700,000 in a work subsidised superannuation scheme. Because of my concerns about a possible financial downturn it has been invested in the conservative (cash) option since 2015, and consequently we have not benefitted from the rising market values in recent years, but also have not lost value with the recent downturn.

I see this downturn as an opportunity to invest wisely when prices are low, and increase the value of our nest egg for the years ahead. How should we manage our superannuation funds wisely?

AAs I’ve said before, buying shares now that the market has fallen is better than selling now. But to do “contrarian investing” well you have to get lucky with your timing.

If you buy too soon, the markets might keep falling as you watch in dismay. But if you wait too long, you’re likely to miss most of the upturn — which can be sudden.

You’ve already had bad luck with your timing. There’s been so much fuss about the recent downturn, and much less about the preceding long share climb, that many people seem to have things out of proportion.

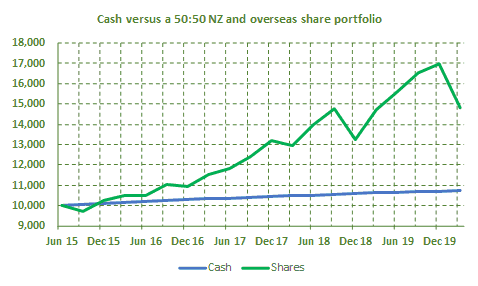

The truth is — sorry to tell you this — that even after this downturn, you would have been much better off if you had been in a higher-risk investment throughout. See this graph:

According to an investment expert using reasonable assumptions, if you had invested $100,000 on July 1 2015, you would have the following, after tax but before fees, last Wednesday (April 1):

- About $107,000 in cash.

- $148,000 in half NZ and half overseas shares.

- $169,000 in all NZ shares.

Do you really want to try your luck again by making a big move now?

I suggest you work out how much of your savings you will spend in the next three years and leave that where it is. Then put your three-to-ten year money in middle risk, and longer-term money in higher risk. That removes the chance your balance will drop lots close to your spending time.

For both moves, transfer the money in, say, three lots, some now, some in a month or two, and some maybe two months later. I’m vague because nobody knows when the market will hit bottom. But by moving gradually, at least some of your timing should turn out to be good.

There’s lots more on setting up your money for retirement in my book, “Rich Enough? A Laid-back Guide for Every Kiwi”.

P.S. Despite your bad lack with earlier timing, you are — as you say — financially fine. And I like your idea of turning your home into two flats. It’s a great way of staying put but making use of all the money tied up in the property.

QI’m 20 years old and work a full-time job. Since starting this job at the end of last year, I have begun planning to save for a deposit on a house. I figure it will take me at least four years if my salary remains the same.

I currently have $8,000 in my savings. With share prices dropping significantly, I was wondering if it could be profitable to invest in some shares while the prices are so low.

What shares would you recommend to invest in at the moment?

AAnother young one with your financial act together — see first Q&A. That’s great.

I like your idea of getting into shares, but I wouldn’t recommend buying shares directly for two reasons:

- There’s no good way to pick which shares will do well — now or ever. The prices of the ones with good prospects will already have been pushed up to the point where they are not necessarily good buys. The best way around this is to get into a wide range of shares in a fund.

- Your time horizon is too short to invest purely in shares. As I said above, money you plan to spend within three to ten years should be in a middle-risk or balanced fund. This holds some shares but also bonds — which waters down the volatility. And when you are within two or three years of buying your house, move to a low-risk fund for the same reason.

As I write this, I suspect you won’t like it. If you want to charge ahead, fully into shares, good luck! After all, if the markets flounder for a while you can always postpone your house purchase.

But whatever you do, be in KiwiSaver. It’s a great place to save for a first home because you get employer and government contributions added to your own savings. After three years you can withdraw all but $1000 to buy the home, and you may get an extra grant from the government. See kaingaora.govt.nz

QI have listened to your advice to not change to a lower-risk fund because shares have fallen, or you realise the loss. I think it’s a great time to instead move to a growth fund from my current balanced fund.

But am I right in thinking that moving to any other fund realises the current losses, and one should just stay in whatever fund they are in until their current fund has recovered all the gains currently lost. I am just worried that could be some time away.

Many thanks for considering this question, I have not seen any guidance on this matter in the media.

AIt’s true that you make a loss real — or “realise” it — if you cash up an investment or move to a lower-risk fund when shares have fallen. If you hadn’t done that, the markets would eventually recover and the loss would disappear.

But you’re considering moving to higher risk. True, you’ll be selling the units in your balanced fund for less than before the downturn. But the price of the units in a growth fund — with its heavier investments in shares — will have dropped even further.

So it’s a good move to make. You’ll realise a loss, but more than make up for that by buying a bargain.

Your thinking shows that you can cope with market volatility — which is one of the “qualifications” for investing in a growth fund. The other is that you don’t plan to spend the money within ten years. If that’s true, go for it!

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let’s keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm is a freelance journalist, a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL), a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. From 2011 to 2019 she was a founding director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won’t publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.