Q&As

QI have run a small portfolio of shares over the last ten years, trying to save for my retirement. It is a mixture of index funds and share picks.

With the Covid crisis and all the money printing going on I was wondering whether traditional financial planning principles still hold.

I have become interested in either gold or even bitcoin as a hedge. The more I read about bitcoin the more I think it will grow due to more people around the world not having a bank account but having a phone.

Do you think putting 1 to 2 per cent of my portfolio into bitcoin would be a good hedge? I’ve got used to the volatility of the markets. I know there is no rhyme or reason to bitcoin going up and down!

AI don’t know. I’ve read about bitcoin, but I don’t really “get” it enough to invest in it myself. But you sound braver or — if you don’t mind my saying — perhaps madder.

Some experts say that if you’re going to invest in anything really different, make it at least 10 or even 20 per cent of your investments. Otherwise, why bother?

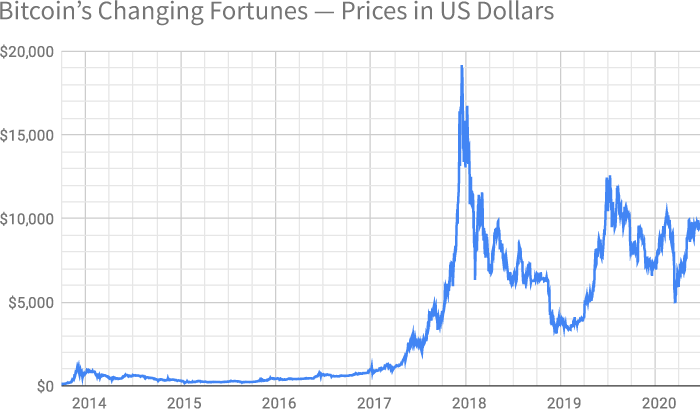

But if it’s something like bitcoin, you’ve got to be prepared to see the value plummet. From late 2017 to late 2018 its value fell more than 80 per cent. See the graph. Ouch!

A drop like that in 20 per cent of your portfolio would hurt. But if it’s only 1 or 2 per cent, it would just be an itch. So why not have a bit in bitcoin, for a bit of interest! (Sorry.)

My only worry is about toes in the water. If that tiny investment does really well, you might get carried away and buy more. Please — only with money you can afford to lose.

On bitcoin being a hedge, that means it tends to move up when other investments fall, and the reverse. But our graph suggests it has a life of its own, rising and falling drastically when share markets were rising pretty steadily. So it seems to be not a hedge, as such, but certainly a diversification.

Comparatively speaking, gold is probably less risky. And it does tend to rise when shares fall, and vice versa. But it’s volatile too. And like bitcoin doesn’t pay any dividends or interest. Take care out there.

QI have recently read a personal finance book (and your book — both good) and in it the author recommends that we don’t fix our mortgage rates as this locks us into one bank. Instead he recommends a higher, floating rate so we can shop around when other lenders offer better rates.

I’ve been trying to balance up paying extra interest versus having the ability to pick and choose which mortgage lender to use.

I’ll be buying a house in Christchurch soon, and will be borrowing around $500,000.

Would you make a similar recommendation for a new mortgage?

ATime to get real.

In theory it would be good to get a floating — or variable — rate mortgage so you can move when another lender is cheaper. However:

- Do you really want to keep monitoring mortgage rates religiously, as opposed to getting on with your life?

- it’s not that easy to switch lenders. There’ll be some hassle and some expenses.

- Most importantly, how do you know that tomorrow your current lender isn’t going to drop its rates to below the new lender?

There’s no way to forecast mortgage rates. But probably the best guide is to look at what they’ve done over recent years.

You can use an online tool for this, on the Good Returns website.

It’s not ideal. When you look at floating rates, for example, many banks offer several different plans, some of which turn out to have no recent data. But playing around with the tool suggests that ASB, ANZ and Kiwibank (in alphabetical order — they are about equal) have tended to offer lower floating rates than BNZ and Westpac since 2015.

You can also look at other banks, fixed rates for different terms, and over other periods. Have a go!

On fixed versus floating, in recent years fixed rates have nearly always been lower. But ten years ago it was the opposite. And Kiwibank has just dropped its floating rates by a full percentage point, bringing the two much closer. Other banks may follow.

I’ve always recommended — as you will have seen in my book — that you get some fixed and some floating.

With fixed, you know where you stand. With floating there’s more flexibility, including the ability to have revolving credit or offset arrangements, and to pay off part or all of the loan at any time. You never know when you might get an inheritance, redundancy pay or other lump sum.

Also, if rates later rise, you’ll be glad you had some fixed. But if rates later fall you’ll be glad you had some floating.

If fixed and floating rates come closer together, more people are likely to have maybe half one and half the other. That’s what I suggest for you.

QJust wondering if you have any insight into the Government thinking around eligibility for their annual contribution to KiwiSaver?

I’ve just signed up for KiwiSaver, now feeling secure enough with my level of mortgage debt to start saving for retirement. I’m a 41-year-old single woman, so I’m well behind the eight ball!

One of the positives to come out of lockdown was savings. I now have enough to put in $1,043 to get me started.

In talking to the IRD though, I’ve found out that the Government’s contribution to my KiwiSaver for this first year (ending 30 June 2020) will be pro-rated based on the number of days I’ve been in KiwiSaver.

I’m feeling a bit disappointed. Although I’m investing the same amount as anyone else in KiwiSaver for the year, I miss out on the full $521 from the Government. Do you know what the thinking was around this?

AI suppose they just said people in the scheme for part of a year deserve only part of the contribution.

But come to think of it, it would be good to give people the full amount in their first year — regardless of when they sign up — to encourage them to join. In the long run, it wouldn’t greatly affect the government’s KiwiSaver costs.

Still, it’s great you’ve joined now, so you’ll be eligible for the full amount from next KiwiSaver year, starting July 1 — and then every year until you turn 65.

Generally I recommend that people with mortgages participate in KiwiSaver enough to get the government and employer contributions, because they really boost savings totals. Further savings can go into reducing the mortgage, but it’s a pity to miss the KiwiSaver incentives over the years.

But you’ve concentrated on your mortgage until now. And given how big some mortgages are these days I can understand that.

Now, though, welcome aboard the good ship KiwiSaver! You still have 24 years to make it work well for you.

P.S. That’s a nice positive out of the lockdown — that you were able to save your first contribution.

QWhy do funds have minimum timeframes e.g. 10 years for my KiwiSaver growth fund. And why do they vary so much between providers with the same investment strategy?

I think many novice investors misunderstand, and it confused me despite working in the industry for many years.

In all Product Disclosure Statements under section 3 “Description of your investment options”, the fund manager is required to include the minimum suggested timeframe for investment.

On looking around I noticed a number in the last few years have reduced their timeframe to 5 years, but there is still quite a range for funds with similar names and asset allocations.

For example, ASB KiwiSaver Growth Fund in 2018 reduced its timeframe to 11 years minimum. Meanwhile Fisher funds say 5 years and Westpac say “long term” for their growth funds. Does that make Fisher Funds safer?

Here’s what I found, looking at growth funds’ current PDS’s:

- Growth assets of 70 per cent: BNZ 10 years.

- Growth assets of 77 per cent: AMP 7 years.

- Growth assets of 80 per cent: Fisher 5 years; ANZ 7 years, SuperLife 9 years; ASB 11 years, Westpac “long term”.

- Growth assets of 82.5 per cent: Generate 5 years.

AThat’s interesting, and a bit worrying.

The reason for the timeframes is to discourage people from investing money they plan to spend soon in a fund in which unit values can drop fast — and not fully recover before spending time.

KiwiSaver growth funds hold between 63 and 90 per cent “growth” assets, which are mainly shares and property. I reckon it’s best not to use these funds for money you expect to spend within ten years.

However, as you point out, some providers disagree.

There are no rules on the length of timeframes. As you say, the product disclosure statements (PDSs) of all managed funds, KiwiSaver and non-KiwiSaver, have to include a minimum suggested timeframe. And the manager must “ensure that the PDS is not likely to mislead, deceive or confuse investors,” says a spokesperson for the Financial Markets Authority.

“The FMA expects that MIS managers have gone through an appropriate process to determine what they include in their PDSs and to ensure that PDS disclosure remains up-to-date.

“We are not aware of any specific issues about suggested timeframes in PDSs.”

I also asked the spokesperson, “Is it OK that an investor who expects to spend their money in, say, 6 years, might reject BNZ because of its 10-year time frame and choose Generate because it says 5 years, when the Generate fund holds a much higher percentage of growth assets?”

The reply: “One fund having a higher percentage of growth assets than another does not necessarily mean it is risker. There is a wide range of risk and return in various growth assets — all are not created equal.”

Fair enough. But it’s interesting to note that in the year ending March 30 — which included the Covid-19 downturn, Generate’s return after fees was minus 1.2 per cent, while BNZ’s was plus 0.6 per cent, according to Morningstar.

While we should never draw conclusions from just one short period, this suggests BNZ’s growth assets are not riskier than Generate’s in a downturn.

The FMA spokesperson added that there are other aspects for an investor to consider, “including whether a fund focuses on a particular sector (such as property or ‘green’ investments) or companies of a certain size (small, medium or large capitalisation businesses), its risk profile (noting not just the investment mix but also the risk indicator and other risks disclosed) and whether this matches their own, how the fund’s performance will be measured, and the maximum loss they feel they can tolerate.

“Some of these factors are personal and some of them will depend on the approach and the information available from the provider.”

I take their points. But it’s not realistic to expect KiwiSaver investors to judge the finer points of the riskiness of a fund’s assets.

I think there should be minimum timeframe rules. For example, any fund with more than 70 per cent of growth assets of any kind should have a timeframe of at least eight years.

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let’s keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm, ONZM, is a freelance journalist, a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. She is a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL) and a former director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it.Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won’t publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.