Q&As

QWhile investment interest rates are at historical lows, is it as disastrous as some investors believe?

Periods of high interest rates are usually accompanied by higher inflation. So while you may be getting a good return from interest, the value of the principal is falling.

As interest is taxed, you are effectively paying tax on the declining value of the principal, decreasing the actual net return.

AThanks for making two important points.

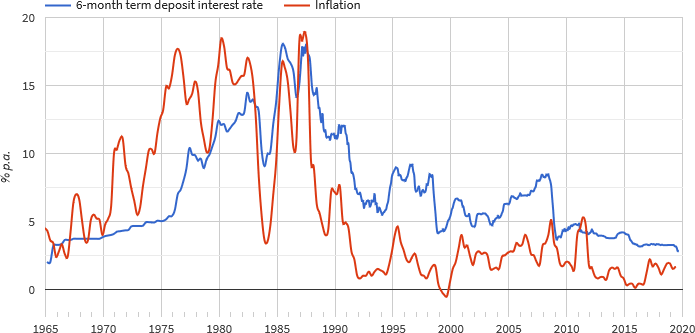

The first is about the link between interest rates and inflation, which is obvious in our graph. The graph also shows that there was a long period in the 1970s and early 80s when inflation — as measured by the consumer price index or CPI — was considerably higher than bank deposit rates.

Back then, while people thought their savings were growing fast, they were actually running to keep up with costs, and failing.

For example, if you deposited $100 at 12 per cent, a year later you would have $112. But if inflation was 15 per cent at the time, $100 of groceries at the start of the year would cost you $115 at the end.

These days, at least your money will buy more at the end of the year than at the start — despite low interest rates.

Your second point is related to the one I made last week, about how we should index tax brackets, so they rise with inflation. Without indexing, when our income rises, we pay more tax even though our income may not buy us any more.

And this is worse when inflation and interest rates are higher. Let’s go back to our deposit earning 12 per cent. If you were in the 33 per cent tax bracket back then, tax would have reduced your interest to 8 per cent — putting you even further behind in terms of buying power.

With current interest at, say, 3 per cent, tax reduces it to 2 per cent, and that will usually still keep you ahead of inflation — even if only slightly.

Conclusion: today’s low deposit interest rates aren’t as bad as they seem.

QUpon retirement I was a prudent investor. Capital was invested as advised in shares, property and bonds. At the time this looked good.

Now bonds are maturing in the next few years, and I’m looking at re-investing at current rates of 2.6 per cent. After taxation and allowing for inflation there is little left for maintaining my lifestyle.

As short-term rates are now offering a better return than longer terms, there is little chance of an improvement.

Do I spend the money on a cruise? Invest in a higher-risk investment? What other options are there?

There must be many more retirees asking themselves the same question.

AI’m sure you expect me to say, “No, no, don’t splurge on a cruise!” But some retired people are too frugal, so maybe blowing a small part of your savings on a treat isn’t a silly idea.

Obviously, though, you need to look after your savings even more carefully than before, given that returns on bonds and term deposits have fallen considerably.

What’s more, as you note, short-term deposits currently pay about the same, or more, than longer-term ones. This is unusual. Normally you get more for locking your money up for longer.

The current situation means experts expect interest rates to fall over the next few years. And while the experts have been wrong before, it would be risky to count on rates rising soon.

So what can you do? Some ideas:

- Increase your risk — carefully. Don’t do this with the money you expect to spend within the next ten years. There’s too big a chance it will be in a downturn when you want to withdraw it.

But you could put your longer-term money in a fund that invests in a wide range of shares. These days you can join a KiwiSaver growth or aggressive fund at any age. Use Smart Investor to learn about what’s available, and pick a low-fee fund.

- If you own a mortgage-free home, perhaps spend your savings by the time you are 80 or 85, and then get a reverse mortgage. That could give you several hundred thousand dollars to spend on cruises and everything else. For more on this, see last week’s column.

- Move to a cheaper house. Or take in boarders. Or subdivide. Or look into rates postponement offered by many councils — rather like a mini reverse mortgage. Or sell your house and become a tenant — no more maintenance worries! Or sell assets. There are many ways inventive retired people free up cash.

By the way, before you feel too sorry for yourself about low interest rates, see the previous Q&A. At least you’re doing better than retired people in the 1970s and early 80s!

That situation probably drove some of them to join the share buying frenzy that led to the 1987 sharemarket crash. Many people broke some investment “rules” then, such as investing in just a few shares, and borrowing to invest without realizing how risky that is. Let’s not do that again, everyone!

QI am a 68-year-old semi-retired widow. Taking advice from your book Rich Enough?, I had happily laddered my term investments.

As they come up for reinvestment, however, the rates of return are getting so low they are starting to really annoy me! They are doing much worse than my KiwiSaver, which, although set at conservative, brought in 7 per cent this year.

So, as the term investments come up for renewal, I have begun to flip them into my KiwiSaver account.

My worry, though, is your warning not to put all eggs into one basket. Is a conservative KiwiSaver fund really a risk? Yours anxiously.

AOnly if you expect it to keep on getting returns of 7 per cent.

Pretty much all KiwiSaver funds have had unusually strong returns in the last few years. Shares have performed really well, but so have bonds — a big component of most conservative funds.

One reason bond funds have performed so well is that interest rates have declined. When that happens, older bonds held by a fund become attractive because they pay higher interest, and their value therefore rises. That is reflected in your high return.

But as interest rates level off — there’s not much further they can fall — that effect will die out.

Also, if your fund holds lots of overseas bonds, there’s been a similar effect from the fall in the value of the Kiwi dollar in the last few years. When our dollar drops, the value of foreign assets rises. That might continue, but it might not.

All in all, then, you should regard your 7 per cent return as exceptional. Over the long run, the return after fees and tax on a conservative fund is more likely to be around 2 or 3 per cent. It could even be negative some years if, for example, interest rates rise fast — the reverse of the recent effect.

Over all, though, your average returns should be a bit higher than on bank term deposits — reflecting the fact that there’s a bit of volatility.

And given you’re in a KiwiSaver fund, which is fairly closely monitored, there’s almost no chance you’ll permanently lose money.

I would put some of your savings — say half — in the KiwiSaver fund. But — given your signoff — you might want to leave half in deposits, which will never have negative returns.

However, consider being braver with some of the money you won’t spend for a decade or more. That could go into, say, a KiwiSaver balanced fund, which should give you somewhat higher average returns over the long term — as my book explains.

QIn regard to your Waihi resident who owns an apartment in Auckland city, there are a few disadvantages in owning apartments compared to residential houses. I have owned an apartment for over 20 years in Auckland.

The first is that the yearly capital appreciation for an apartment is much less. An apartment may double in value every 20 years — a poor return compared to recent housing statistics.

The next is that body corporate levies, which do not include council rates, tend to be much higher than normal homeowner expenses, as they include the costs of the management/administration. And in my experience these fees double every 10 years.

Finally, the net rental return of an apartment, based on the cost of investment and after expenses, is normally about 3 to 4 per cent a year, which is a lot less than an investor can receive from say managed share funds.

The advantage is of course that the apartment owner can never be priced out of his apartment if house prices escalate. But this needs to be compared to returns from other investments such as bonds, deposits and share funds.

AGood tips from the voice of experience.

I doubt, though, that apartments will always appreciate more slowly than houses. True, the apartment market is somewhat different, and has probably been affected in recent years by a bigger increase in the supply of apartments than houses.

But if apartments became hugely cheaper than houses of a similar quality, demand would rise for them, pushing their prices up. I’m sure there will be periods in future when apartment prices outpace house prices.

It’s interesting, though, that the two markets can apparently get quite out of whack at times.

Your mention of body corporate levies reminds me that I’ve heard plenty of stories from apartment owners struggling with body corporate disagreements. It’s hard to get everyone on the same wavelength when it comes to, say, expensive long-term maintenance, or improvements that some owners don’t think will improve anything.

It seems that when people sell their home and buy an apartment they trade one set of complications for another. Sigh.

QI beg to differ about your comment last week: “If our tax system had true integrity, mortgage interest should actually be deductible for everyone with a mortgage, not just landlords — given that all the interest we receive is taxable.”

Clearly this should not be the case, as taxation principles require sufficient nexus (link) between income and expenditure. As owner occupied rent is not income, then mortgage interest cannot be tax deductible.

Making such a change would create a new set of issues. Note that although mortgage interest is deductible in the USA, this causes another raft of problems. For example, home owners (not just investors) pay capital gains tax on the sale of their house and again anomalies can occur in this.

AAnd I beg to differ — about the US situation! In many cases Americans don’t pay capital gains tax when they sell their homes.

But let’s not get into that. Your main point is fair enough. When I moved back to New Zealand from the US, it seemed unfair that mortgage interest wasn’t deductible here. But I understand what you’re saying.

By “owner occupied rent” you’re talking about the fact that homeowners live in their homes, and that’s a benefit — like income really — that they don’t pay tax on.

This is sometimes called imputed rent. Various experts have at times suggested it should be taxed as income, as is done in some European countries. Presumably in those countries mortgage interest would be deductible.

Another reader made a similar point: “The home mortgage could be deductible if you were also taxed on the accommodation benefit you receive — an "imputed rent" that you don't need to pay because you own. Would certainly generate my property accounting business some extra work!”

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let's keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm is a freelance journalist, a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL), a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. From 2011 to 2019 she was a founding director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won't publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.