Q&As

- Why 20 shares are much better than two.

- Reader claims diversification is not a great idea. I disagree.

- Is land a lower risk investment than a share fund?

QI have started to make a small share portfolio in the following companies: Auckland International Airport and Briscoe Group.

I am wondering whether it would hurt to either invest more into these two over time or look at buying another small amount in a third listed company, or even investing the same amount I have in shares into a fixed interest investment.

What are your thoughts on this?

AMy first thought is: good on you for venturing into shares. Too many New Zealanders are overly scared of them.

My second is that at least you are in two companies, as opposed to the one-company portfolio so common among New Zealanders who do own shares.

But I would far rather see you in ten different companies — preferably in ten industries and including large and small companies. Twenty would be better still.

It’s all about the relationship between risk and reward.

Usually, the more risk you take the higher the expected return. But there is one situation in which risk and return don’t go hand in hand. That’s when you buy just one or a few shares — or finance company debentures or whatever.

Let’s say the expected return on shares — including dividends and price gains — is 10 per cent a year.

We would expect that over the years the average return on your two-share portfolio would be around 10 per cent. But, given that you’re holding just two companies — and both wonderful and terrible things can happen to companies — your returns might range from 50 per cent some years to minus 30 per cent other years.

Note that this is not a comment on Auckland airport or Briscoes. I have no idea how those shares will perform, and I don’t have much faith in other people’s forecasts of any particular share.

Now let’s say you buy about 18 more shares. Our expected average return on your portfolio would remain 10 per cent. But we would expect the range of returns to be much smaller — say 30 per cent to minus 10 per cent. That’s because when some companies did badly it’s likely that others would do well.

You would be riding much gentler waves. That not only makes it easier to sleep, but also reduces the chance that, if you unexpectedly need to take out your money, it won’t be deep in a trough at the time. Your risk is lower, but your expected return is unchanged. This has been called the only free lunch in investing — and a tasty one it is too.

At a practical level, owning 10 or 20 shares can be too expensive when you are starting out, as there are minimum parcels you can buy.

One way around that is to invest in a share fund until you build up enough to buy a wide-ranging portfolio. Sure, you pay fees to the fund managers. But this is partly offset by the lower brokerage paid by the big players. For those with limited savings, the advantages of diversification in a share fund easily outweigh the higher costs.

I would normally add that you could get into a share fund via a certain new saving scheme starting with K, and cash in on the government kick-start and tax credits. But I promised not to write about that this week!

One more point: Even if you own 20 different shares, you still won’t get great diversification if a large portion of your portfolio is in just one or a few companies. Try to have roughly even holdings, selling some shares in any holding that grows much faster than the others.

QI recently saw a cartoon that shows a husband telling his wife, “Yes, our investments are diversified: 20 per cent out the window, 65 per cent down the drain, and 15 per cent gone with the wind.”

I have a NZ certificate of investment analysis, which I obtained while I was a manager at the NZ Stock Exchange during 1987. One question in the final exam, about a week after October 19th, begged the answer “Diversification through international shares.”

Of course, all share markets fell in the crash, and diversification both in sector and internationally was no protection from the meltdown. The question, in hindsight was a joke. Diversification is not necessarily an answer to protection of assets.

Other investment advice, no less valid, is “Put all your eggs in one basket and watch that basket.”

AThat advice is all very well for the man who said it, US steel magnate Andrew Carnegie — said to have once been the world’s richest man. He could hire any number of analysts to keep an eye on his investments.

For Joe and Joanne Blow, however, such vigilance is impossible — and not only because they have other things to do with their time.

If they invest in a publicly listed share, generally they won’t hear new information about the company until it’s too late to do them any good. The big institutions will have already sold on bad information and pushed the price down, or bought on good information and pushed the price up. And if Joe and Joanne happen to pick up insider information, it’s illegal for them to trade on it.

True, they could invest in a private company and keep a close eye on it. But that’s no guarantee of success. Such investments are like the little girl with the curl in the middle of her forehead. When they are good they are very, very good, but when they are bad they are horrid.

So where does that leave us on diversification? You’re quite right, when a market crashes, it takes all shares or properties or whatever down with it. However:

- Any investor in a volatile asset like shares or property should have at least ten years in hand before they expect to spend the money. Over ten years — often much less — almost all markets recover from crashes. If you expect to spend the money in less than ten years, go for less volatile assets such as bonds.

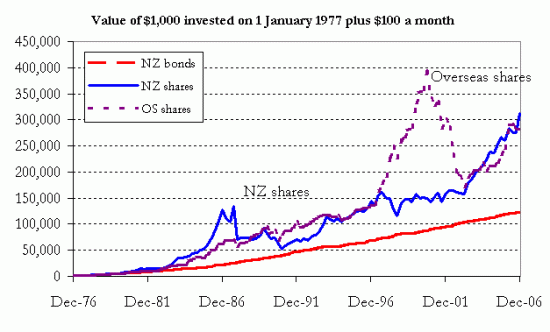

- It’s wrong to say international diversification didn’t help in the 1987 crash. As our graph shows, while world markets did indeed dive, they recovered much faster than New Zealand. Anyone with half their share portfolio offshore fared much better than those who stayed local.

- The graph also shows the reverse early this decade. International shares plunged but the New Zealand market recovered quickly.

- If you want to even out the wobbles, diversify beyond lots of shares, local and offshore, and also invest in property and bonds. While different types of assets sometimes fall at once, often a gain in one will offset a loss in another.

If we’re quoting Carnegie and nursery rhymes, we might as well add Winston Churchill’s quote: “It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except all the others that have been tried.” I reckon diversification is the worst way of investing except all the others that have been tried.

PS. Churchill also said, “The best argument against democracy is a five-minute conversation with the average voter.” But that’s another story.

QWhat do you think about investing in land? I am thinking of investing for 10 years or over.

At present I have my money in managed share funds — and I am wondering if land is more secure, less prone to fluctuations.

AGenerally, property has lower risk and lower returns than shares. But there are two “however”s.

Firstly, borrowing to invest in anything raises both the expected return and the risk. If you use a mortgage — especially if it’s for most of the purchase price — the investment may well be riskier than a share fund.

Secondly, like the reader in today’s first Q&A, you will be undiversified unless you buy several pieces of land.

People often say land doesn’t lose value, but that’s nonsense. Anything can happen. Zoning is changed; soil contaminants are discovered; a big employer moves away so the local economy suffers; the nearby high school deteriorates under a new principal; or a neighbour builds to block your view.

Or how about this? You invest in a “safe” upmarket suburb, in which many property owners invest in shares. The share market crashes, and lots of neighbours are forced to sell and buy cheaper homes. Property prices plunge. Sounds far-fetched? It happened after the 1987 share crash, pushing some house prices down more than 30 per cent.

More broadly, the whole property market can fall, as we’re seeing now in parts of the US, UK and even New Zealand.

It wouldn’t be at all surprising to see the value of the land on which most New Zealand homes sit falling in the next few years. We don’t sell our homes every day, so we don’t realise their volatility.

So what should you do? If you can buy several sections around the country, without mortgages, land will probably be less risky than a share fund. Otherwise, I suggest you stay put.

CHARITABLE CHRISTMAS GIFTS

This column recently included a list of charities through which you can buy gifts on behalf of your friends or relatives that are given to needy people overseas. I’ve since heard that Save the Children — at www.wishlist.org.nz or 0800 167 168 — also offers such a programme.

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let’s keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm is a freelance journalist, a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL), a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. From 2011 to 2019 she was a founding director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won’t publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.