Excerpt from The Complete KiwiSaver

Which Assets Are for You?

This week, Mary Holm’s Q&A column is replaced by an excerpt from her latest book, “The Complete KiwiSaver”. The principles she discusses here apply not just to KiwiSaver but to investing in general. Her Q&A column will resume next week.

ALL SHARES, ALL BONDS, OR SOMETHING IN BETWEEN?

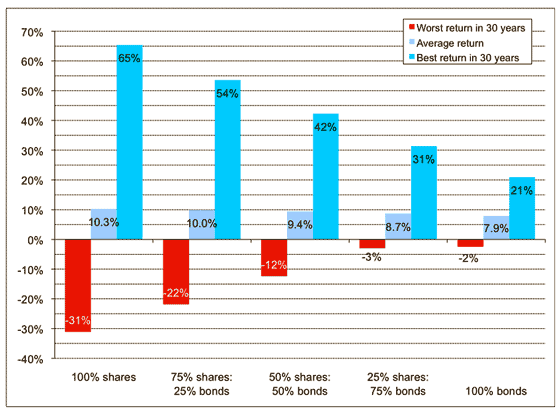

(Graph source: MCA and MSCI, NZX. Returns are after 30 per cent tax. Bonds are NZ bonds, shares are 80 per cent overseas (of which 50 per cent are currency hedged) and 20 per cent NZ.)

Our graph shows what would have happened over the 30 years ending January 1, 2009 if we had had five KiwiSaver funds, ranging from all shares on the left, through mixtures of shares and bonds, to all bonds on the right. The higher the proportion of shares, the wider the range of returns — but the higher the average return.

Some KiwiSaver funds, with names such as “conservative” or “low-risk”, invest fully or largely in bonds and/or cash. Others, which might be called “growth” or “higher-risk”, invest largely in shares and/or property. In between are “balanced” schemes — although their composition varies somewhat from provider to provider.

The higher-risk or growth funds will have big losses some years — as we have seen recently. But over the long term their average returns will almost certainly be higher. See the graph.

Which mix of assets is best for you? How much risk you take on should depend on four factors:

How long you will be investing.

If you expect to buy your first home within ten years and make the most of the KiwiSaver first home incentives, or you have less than ten years before you plan to spend your KiwiSaver money in retirement, you are probably best to go with a scheme that invests mainly in lower-risk assets such as high-quality bonds.

If you were to choose a scheme with lots of shares and/or property, it’s quite possible that when you wanted to get your money out to spend, there would be a market slump and you’d get less than you expected.

As you get to within two or three years of spending the money, it’s a good idea to move to an even lower-risk fund, such as a cash fund.

Chances of your account balance falling

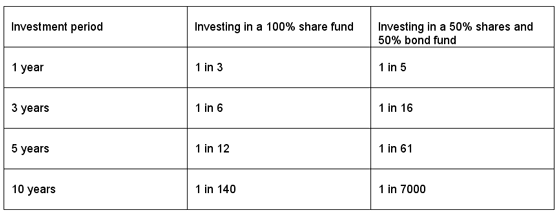

(Table source: MCA. Returns are after 30 per cent tax. Based on NZ and international data over the last 30 years.)

Our table shows how much less likely you are to suffer a loss in a halfway fund — 50 per cent shares and 50 per cent bonds — than in a 100 per cent share fund. This is partly because bonds are less volatile than shares. But it is also because there’s some tendency for shares to do well when bonds do badly and the reverse, so there is a balancing effect.

Over a single year, or even three years, there’s a pretty high chance your account will fall in a share fund. By the time you get to ten years, though, the chance is tiny. In a bond fund, your odds look pretty good over just three years. And after ten years, history suggests you are more or less guaranteed not to lose.

However, what this table doesn’t show is how much faster your money is likely to grow in the 100 per cent share fund over the long term. Let’s assume a share fund might grow at 8 per cent a year after fees and taxes, and a 50:50 fund might grow at 6.5 per cent.

Higher return makes a big difference over the long term

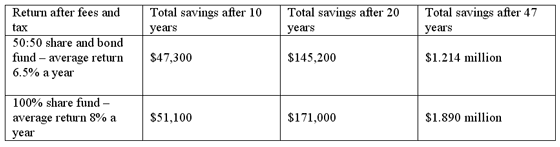

Assume an employee earning $50,000 contributes 2 per cent to KiwiSaver. She receives the $1,000 kick-start plus tax credits and employer contributions. Her salary rises by 3 per cent a year.

The trade-off is clear. After 10 years there’s not a huge difference in total savings at the different return rates, but after 20 years the difference is appreciable. And if our employee saves all the way from age 18 to 65, for 47 years, her savings will be more than one and a half times as big in the share fund.

If you have a longer time horizon, it’s a good idea to invest in a riskier fund — perhaps largely shares and/or property. You’ll probably end up with much more than in a conservative scheme.

A note on approaching retirement: Generally, as people approach retirement, they tend to move their savings to less risky assets. But that doesn’t necessarily mean you should put all your KiwiSaver money in a conservative fund.

Your retirement may well last 20 or 30 years, or even longer. If you are planning to spend some of your KiwiSaver money later in retirement, you may want to invest that portion in a somewhat riskier fund in the meantime, and then gradually move the money to a more conservative fund as you get within about ten years of spending it.

How well you cope with ups and downs.

Even if you have many years to play with, it’s not a good idea to invest in a riskier fund if you are likely to panic when your account balance falls.

If there’s one thing we know about the movements of share and property markets, it’s that we don’t know where they will go next — and as we all saw in 2008, every now and then it will be sharply down. While history shows that these markets always recover eventually, nervous investors tend to bail out after a plunge — which in KiwiSaver would mean switching to a more conservative fund — and thus turn paper losses into real losses.

When the share market or property market is down, that is exactly the wrong time to get out of an investment. Those who do bail out will end up with less savings than those who started out in a more conservative fund.

Here’s a good test: Imagine a year in which your KiwiSaver account balance halves. Occasionally that happens in a share fund. Could you hang in there? If not, you are better to start out with a lower-risk fund, perhaps gradually moving to something riskier as your confidence grows.

One way to boost your investment courage might be to put the money you personally contribute to KiwiSaver into a lower-risk fund, and the government and employer contributions into a higher-risk fund.

If the latter does poorly, you can console yourself with the idea that you wouldn’t have had that money anyway if you hadn’t been in KiwiSaver. Easy come; easy go!

Your provider may not keep track of which of your inputs come from where, so you may need to give them guidance. If you are a non-employee contributing $1,043 or less a year, after the first year half your inputs are from you and half from the government, so just tell your provider to split your money half and half.

If you are an employee earning less than $52,150 and contributing 2 per cent of your pay, after the first year one third of your inputs are your contributions and two-thirds come from the government and your employer, so you could go with one third low-risk, two-thirds high risk. People earning more than that fall somewhere in between, so they could just go with one-third/two thirds or half and half.

What about the first year? That’s when you get the $1,000 kick-start, so in that year a higher proportion of the inputs are from others. But it’s not worth mucking around with. I suggest that you use either 50:50 or one third/two thirds from the start. Ignoring the kick-start in this situation will make little difference in the long run.

What other savings you have.

You can reduce your risk by investing in a wide range of assets. When one type of asset does badly, another might do well.

Clearly, then, you should take other investments into account when choosing a KiwiSaver investment. For example, if you own investment property, it might be good to avoid property in KiwiSaver. Or if your other investments are lower or higher risk than you want at this stage in your life, you might balance that out by making your KiwiSaver investments nearer the other end of the risk spectrum.

How much money you have at stake.

Let’s say you invest only a small proportion of your total retirement savings in KiwiSaver. If you’re not an employee, it might well be just $1,043 a year.

There’s a school of thought that says you might as well invest in a high-risk fund, so that there’s a chance the balance will grow to something worth bothering with. Note, though, that there’s also a chance, especially over just a few years, that you’ll do abysmally. Do it with your eyes open.

A key point about timing markets: KiwiSavers who are newcomers to the share, bond and commercial property markets sometimes think they’ve discovered the path to riches. ‘I’ll switch into a share fund when that market is down, stay in there until it reaches a peak, and then switch out of shares — perhaps into property or bonds if they are down at the time. Then I’ll ride that market to its peak, too…’

It all sounds so easy. But believe me, it’s not just difficult, it’s impossible.

Lots of research shows that trying to time markets is a fool’s game. The fact is that nobody knows, at the time, if a market is going to go higher or lower. It’s far smarter to find the right asset mix for you, based on the principles set out here, and to stick with it, regardless of what markets do.

No paywalls or ads — just generous people like you. All Kiwis deserve accurate, unbiased financial guidance. So let’s keep it free. Can you help? Every bit makes a difference.

Mary Holm is a freelance journalist, a director of Financial Services Complaints Ltd (FSCL), a seminar presenter and a bestselling author on personal finance. From 2011 to 2019 she was a founding director of the Financial Markets Authority. Her opinions are personal, and do not reflect the position of any organisation in which she holds office. Mary’s advice is of a general nature, and she is not responsible for any loss that any reader may suffer from following it. Send questions to [email protected] or click here. Letters should not exceed 200 words. We won’t publish your name. Please provide a (preferably daytime) phone number. Unfortunately, Mary cannot answer all questions, correspond directly with readers, or give financial advice.